originally published January 8, 2012

In December, 1835, Edgar Allen Poe’s footprint on the literary world was so fresh, pre-Victorian hipsters would have proudly nailed down this period as the time they started reading him, before “The Raven” topped the hit parade and everyone knew about him.

He had won a minor prize for a short story and in August, 1935, he snagged a sweet gig as assistant editor of the Southern Literary Messenger, only to get canned for drinking on the job. This was pre-Hemingway, before it became widely accepted that any writer who doesn’t drink whilst working is probably not trying hard enough.

He returned to the job soon after, claiming his drinking was medicinal, that he suffered from chronic sobriety and this was the only cure. His bosses accepted the excuse, and by December, Poe was ready to unleash a piece of theatre upon his audience. This was more of a shock than Dylan playing electric at Newport. This was more like if Dylan had joined the New York City Ballet. The end result was, just as predictably, a disaster.

Politian would come to be Poe’s first and last written drama. Even then, it wasn’t finished. He published the first segment of the play in the Messenger in December, the second in January, and the third never.

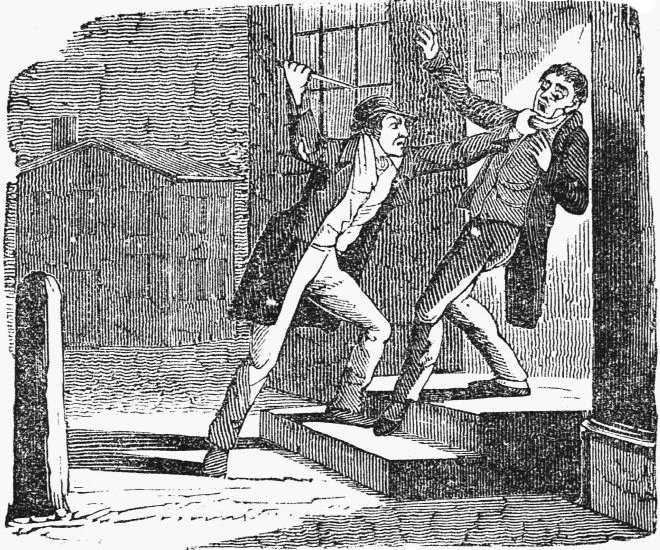

Poe based the play on actual events: a juicy piece of tabloid-topper from 1825 in Kentucky. It seems the Solicitor General of the state, Solomon P. Sharp, knocked up a local strumpet known as Ann Cook. She had his baby, then married Jereboam O. Beauchamp because his name was pure awesome.

As part of the ‘marriage agreement’, Ann talked Jereboam into murdering her baby-daddy. Jereboam, clearly not the fluffiest Peep in the Easter basket, obliged, stabbing Sharp to death. He pleaded not guilty, but the She-Told-Me-I-Had-To defense was not effective, and he was sentenced to hang. This is where things get weird.

Cook visited Beauchamp in his cell shortly before the scheduled execution. They tried unsuccessfully to bribe the guard to let them escape. The two of them swallowed a sizable amount of laudanum, a morphine-based liquid, in a double-suicide attempt. They tripped balls for a few hours, but failed to die.

Not feeling as though she’d failed enough for one lifetime, Cook tried to off herself again, the same way, the night before her husband was set to hang. Nope, she survived. The following morning, she went to visit her husband in his cell, and they stabbed themselves with the knife she had smuggled in.

Her third time was a charm, but Beauchamp was only on his second, and it didn’t take. He had a knife, and couldn’t figure out how to kill himself with it. This was not one of Kentucky’s over-achievers. He was dragged off to the gallows and strung up, because while it was likely he’d eventually bleed out from his wounds, the state had already paid the hangman and the rental fee for the rope was non-refundable.

Poe, who had a certain penchant for dark and dreary prose, felt this would make a magnificent piece of drama. Myself, I’d have gone for slapstick. This story has more non-suicides than Harold and Maude.

For whatever reason, Poe relocated the events of the story to sixteenth-century Rome. Politian, the title character, was the re-imagining of Beauchamp, though why you’d throw away a killer name like Jereboam is beyond me.

One thing I don’t understand is why Poe would publish a portion of his work (which he titled ‘Scenes from an Unpublished Drama”) when it wasn’t completed. The second piece went up a month later, and the critical reviews were Ishtar-bad.

One critic wrote: “Why does Mr. Poe throw away his strength on shafts and columns, instead of building a temple to his fame?” I don’t know what this means exactly, but it sounds scathing. This was Poe’s Phantom Menace. It was his 1941. His Ernest Saves Christmas.

Even Poe’s biographer crapped all over this play, saying that Poe’s knowledge of the period in which it takes place wasn’t up to snuff, and that his protagonist is ‘wooden’. Poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning said that “Politian will make you laugh”, despite the play containing no intentional comedy, just a lot of jealousy and death.

After the second instalment was granted a single-digit store in the public’s collective Rottentomatoes, Poe’s friend and literary peer John P. Kennedy gently suggested that Poe quit trying to be a playwright, and focus on what he does best. Poe’s first and only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket was also a critical bust, and Poe sagely took Kennedy’s advice and kept clear of trying new genres.

Almost a century later, the play was actually brought to the stage. The Raven Society, a group of Poe-centric folks at the University of Virginia (where Poe had briefly attended), decided the play should be finally performed for an audience. I’m not clear on whether they wrote in an ending, or if they just left everyone hanging while the Ann Cook character was petting the floor in a morphine-induced euphoria, naming it Pedro and wondering if tasted like boiled cornhusks.

I’ve glanced at some of the script, and while I hate to give a review without fully ingesting a piece of drama (though, for the purposes of this project, I find that I am doing that a lot), I have to say it’s intriguing, but not enough so that I’ll sit down and read the entire thing. Here’s a sample of dialog, spoken by Lalage (the Ann Cook character):

I cannot pray! – My soul is at war with God!

The frightful sounds of merriment below

Disturb my senses – go! I cannot pray –

The sweet airs from the garden worry me!

Thy presence grieves me – go! – thy priestly raiment

Fills me with dread – thy ebony crucifix

With horror and awe!

Fun stuff. The story was interpreted in a few scattered pieces of fiction and true-crime over the years, but never by an author with Poe’s street-cred.

Maybe he should have tried ballet.