originally published January 5, 2012

Today we journey across the ‘pond’, eat some ‘crisps’ then take a ‘lorry’ to a small ‘towne’ in southern England called Leckhampstead. Knowing those crazy Brits as I do (and I know three or four of them), they’ll pronounce it “Leckumsted”. It’s a beautiful language – I encourage everyone to learn some.

Leckhampstead is in Berkshire, part of the North Wessex Downs. This may seem confusing to we ‘Colony Folk,’ who tend to group by town, state/province, and that’s it. To clarify, Berkshire is the county, and the North Wessex Downs is an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB – it’s a real designation). I guess this would be the English equivalent of ‘The Tuscany Region’ or ‘The Boring-As-Shit-To-Drive-Through Middle Chunk of Canada’.

The town itself is beautiful. If you’ve never been to England, and you think all those quaint thatched-roof homes and cozy-looking churches are just a publicity front, you would be mistaken. Roughly 76% of my week in England last year was spent remarking out loud how drab and un-cute my hometown of Edmonton, Alberta is by comparison. The rest of my time was spent calculating the currency conversion for a sandwich at Pret-A-Manger.

Leckhampstead is as pleasant as any part of England I have seen. The Church of St. James is filled with almost enough multi-colored bricks and overwhelming quaintness to convert me. It was built in 1859, and designed by noted British Architectamundo (which is an obscure Royal Designation for architects) Samuel Sanders Teulon. Teulon designed a lot of gothic-revival churches, but also schools, cottages, and the entire village of Hunstanworth. That’s right, one architect was commissioned to design a vicarage, stable block, a school, a school house (which is apparently different from a school), and a bunch of houses. Had this village been designated as an official Walmart-Dependent Community, Teulon would have probably designed the housewares department.

The public house (or ‘pub’, or ‘booze joint’) in town is called the Stag, and it looks like a delightful place in which one can strap on some ales and drink until one ‘upchucks the bullocks’, as they (probably) say.

The Leckhampstead war memorial is something to see. It consists of a somewhat phallic – or that might just be my interpretation, so my analyst tells me – obelisk with two clock faces. The clocks contain pieces of ammunition in them, and the whole thing is surrounded by chains taken from a battleship and supported by shell casings. I checked out a few other war memorials in Europe, and this is actually one of the more creative efforts. Nothing like what you’d find in the former Yugoslavia, but still, quite impressive.

About a mile south of the village you’ll find a boundary stone known as The Hangman’s Stone. No quaint English village would be complete without a quaint English folk story, commemorated by a slab of rock. According to the tale, a sheep rustler was wandering home with a stolen sheep slung over his shoulder, secured by a rope. He got a little sleepy (sheep rustling is hard work, believe me), then sat on this stone to rest. The sheep, sensing it was time to retaliate, tried to get free. In a move that was totally ripped off by Princess Leia, the sheep wrapped the rope around the guy’s neck and killed him.

I don’t want to crap all over a cozy English folk story, but I have a few unanswered questions about this. First of all, there is no hangman in the story. They should rename that rock The Hanged-Man’s Stone, or possibly the HangSheep’s Stone. Also, once the sheep triumphantly killed the thief, it was still tied to the rope that was now wrapped around a corpse’s neck. Either the sheep was stuck until it starved to death, or was found by somebody else (“Hey cool! Free sheep! Jolly good!”), or else it was the world’s smartest sheep, and found a way to escape and live a full, sheep-y existence with a rope tied to it. Even more reason to re-name the stone after the damn sheep.

There’s a lot of history in Leckhampstead. A flint arrowhead from the Bronze Age was discovered around this area, along with a 2nd century Roman earring and what might either be a Roman Empire-era fondue pot, or possibly an incredibly early prototype of Hungry Hungry Hippos.

There are remains of an eleventh-century church not far from the village, and a medieval deer park was in the area in the 1200’s. This was a fenced-off area in which noblemen could hunt deer sportingly, without the inconvenience of the deer having any possible chance to escape alive.

Leckhampstead is referenced in the famous Domesday Book, published in 1086. I was excited to learn this, hoping it was an early-English spelling of ‘Doomsday Book’, and that it contained an elaborate plan to take over the world, one British sheep-honoring village at a time.

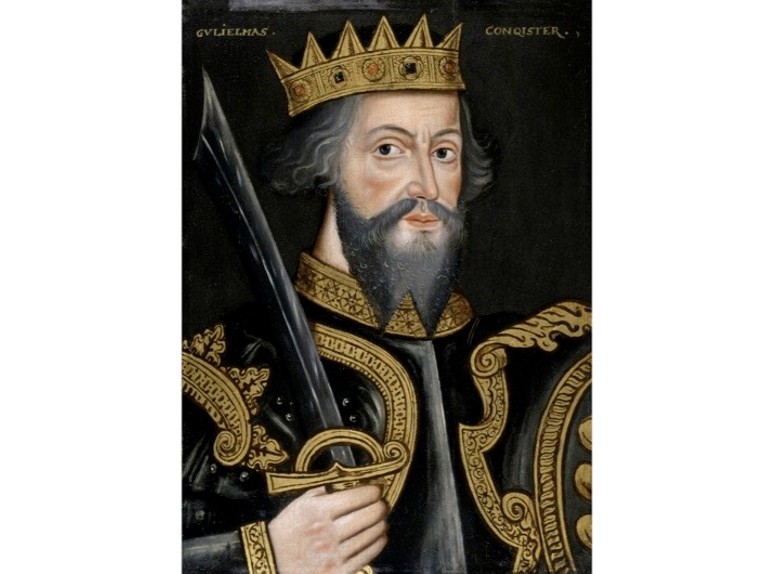

The real story behind the Domesday Book is less exquisite, but nonetheless subversive. William The Conqueror was relaxing over Christmas in 1085, sipping his eggnog-like mead and plotting his New Year’s Conquering Resolutions, when he dispatched his goons to survey England and record who owned what, and what it was worth. Essentially, it was a country-wide tax audit.

The survey came to be known as the Domesday Book, which meant “Book of Judgment”. It seems that, whatever Bill’s goons claimed you owned (and thusly owed in generous taxes), that was the bottom line, no appeal. The cities of London and Winchester were not included in the survey – this was a strike at the heartland, a grab at the little guy’s farm money.

While a great deal of the book is devoted to the nano-details of who owns what – which makes it a valuable historical resource, but a tremendously dry read of Beowolf proportions – a lot of it is about the process of valuation of real estate in the eleventh century. A real page-turner. I’ll post a more thorough review as soon as they release the audiobook, voiced by Samuel L. Jackson.

According to the Domesday Book, Leckhampstead had land for 11 ploughs, and was worth ten pounds.

I’d pay at least double that just for the SuperSheep.